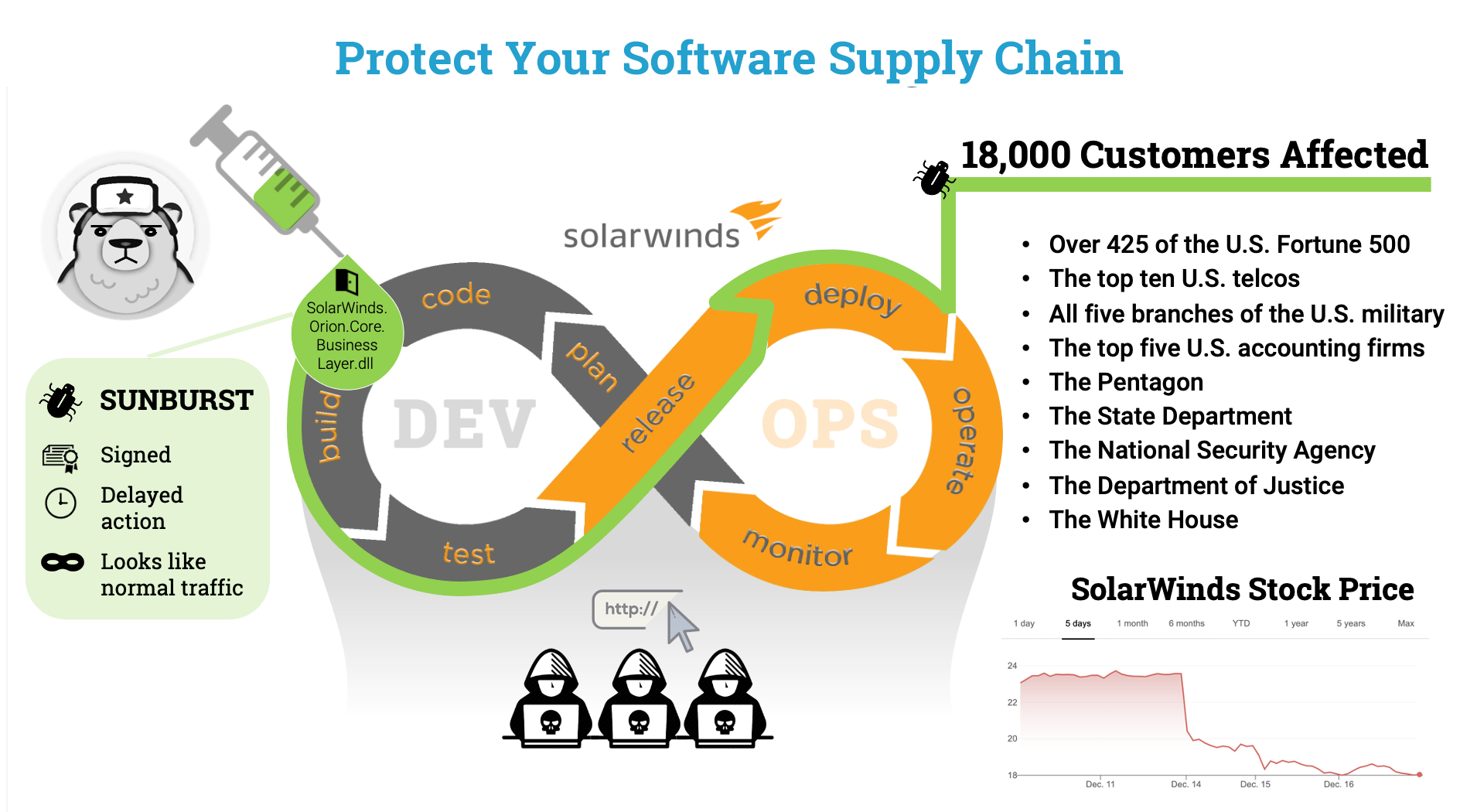

Just in case you missed it, a software supply chain attack on the US government and industries is consuming the waking hours of everyone involved in cyber security this week. The attack involved the insertion of a compromised DLL infected with the SUNBURST malware directly into the DevOps environment of SolarWinds’ Orion network monitoring and management software. It was a cunning and subtle infiltration: the package was signed with a valid certificate, it checked that its process name hash was set to a specific value, and it waited around two weeks before calling home.

Maybe there is some security tool out there that could have detected SUNBURST, but the reality is that 99.9% of the available tools won’t. If they could have detected it, SUNBURST would have been discovered and exposed long ago, not nine months after it was unleashed by the attackers.

This blog is not going to tell you that there is a silver bullet out there. There isn’t. Supply chain attacks are very difficult to detect. But the lack of an easy solution doesn't mean we can't learn from the attack (and make life much more challenging for the next attacker). So in this blog I will highlight what we can learn from this incident and what we should consider as we go forward to reduce the risk to software supply chains.

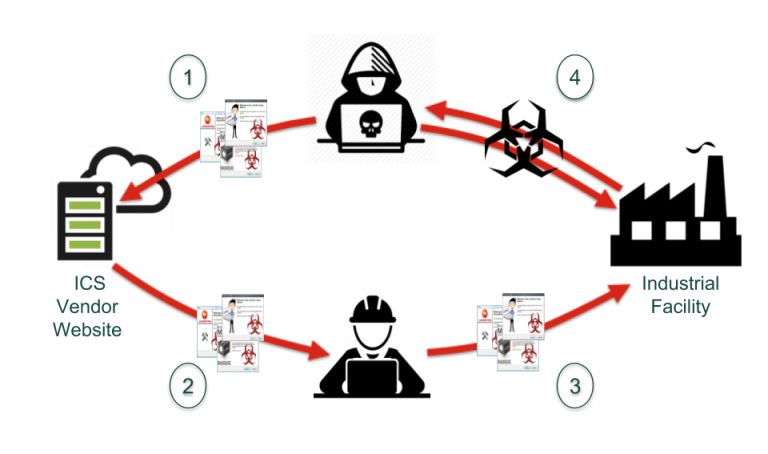

First, this attack is not an isolated incident. In 2014, we saw a similar supply chain attack against the energy and pharmaceutical industries in Europe. These attacks, known as the Dragonfly attacks, allowed the attackers (who very likely are associated with the SUNBURST attackers, if not the same people) to gain a foothold into hundreds of industrial plants by modifying the software being released by three European ICS product vendors. Just last month we saw trojanized security software hit South Korea users in a supply chain attack that, like SUNBURST, also involved signed code. And if we go way back to the grand-daddy of ICS cyber attacks, Stuxnet was (in part) a supply chain attack using stolen code signing certificates. All of this is just the tip of the iceberg: according to the report 2020 State of the Software Supply Chain, supply chain attacks have surged this year, up 430% in the past 12 months.

Clearly supply chain exploits are now a core tool in the cyber-weapons toolbox, especially if the attacker is from or sponsored by a nation state. In the words of the researchers at the internet security company ESET, "Attackers are particularly interested in supply-chain attacks, because they allow them to covertly deploy malware on many computers at the same time.” We observed the same high "attacker return-on-investment" for the Dragonfly perpetrators — by successfully penetrating one mid-tier ICS product supplier, they got deep access into an estimated 280 industrial facilities.

The second takeaway is that software code signing alone is poor defence against supply chain attacks. In all but the Dragonfly attacks, the attackers signed the malicious code with a valid signing certificate. In the SUNBURST and Stuxnet cases, the attackers likely penetrated the supplier’s development operations and stole the signing keys, but in the Korean attacks, the bad guys created dummy companies (one a US branch of a Korean company) and signed the code with those companys’ keys. This second technique is a lot easier to pull off and sadly almost as effective, because most systems don’t check the quality of the signer; the simple fact that the software is signed by someone is enough. It’s like airport security accepting your passport for Disneyland as being as valid as a passport issued by the government.

On a related note, I’m worried that some of the promoters of Software Bill of Materials (SBOMs) are overstating what vendor-generated SBOMs would have done to prevent this train wreck. IMHO if the actors can modify a software release to both include their "special features” and have it signed with a valid certificate, then modifying the produced SBOM is a piece of cake. I wouldn’t rely on an SBOM from SolarWinds right now if you paid me.

The third lesson is that if it’s poorly managed, the solution can be the problem. Remember, SolarWinds is a network monitoring product used for security purposes at many companies. If you look at the list of TCP ports that are required for SolarWinds products to operate, you’ll see that it numbers in the hundreds. Every one of those TCP connections increases the attack surface. In this case, the attackers didn’t use that multitude of communications services to get into their victims' systems, but they sure exploited them to call home. The SolarWinds product might do a good job of network monitoring, but its chaotic design exposes its customers to a lot of unnecessary risks.

To be 100% clear, I am not saying that code signing, SBOMs, or network monitoring are bad. I’m a big proponent of all three as critical tools in our cyber-defence toolbox. My company even generates SBOMs for ICS software companies. But SBOMs or code signing or the tool "du jour" are limited when used on their own.

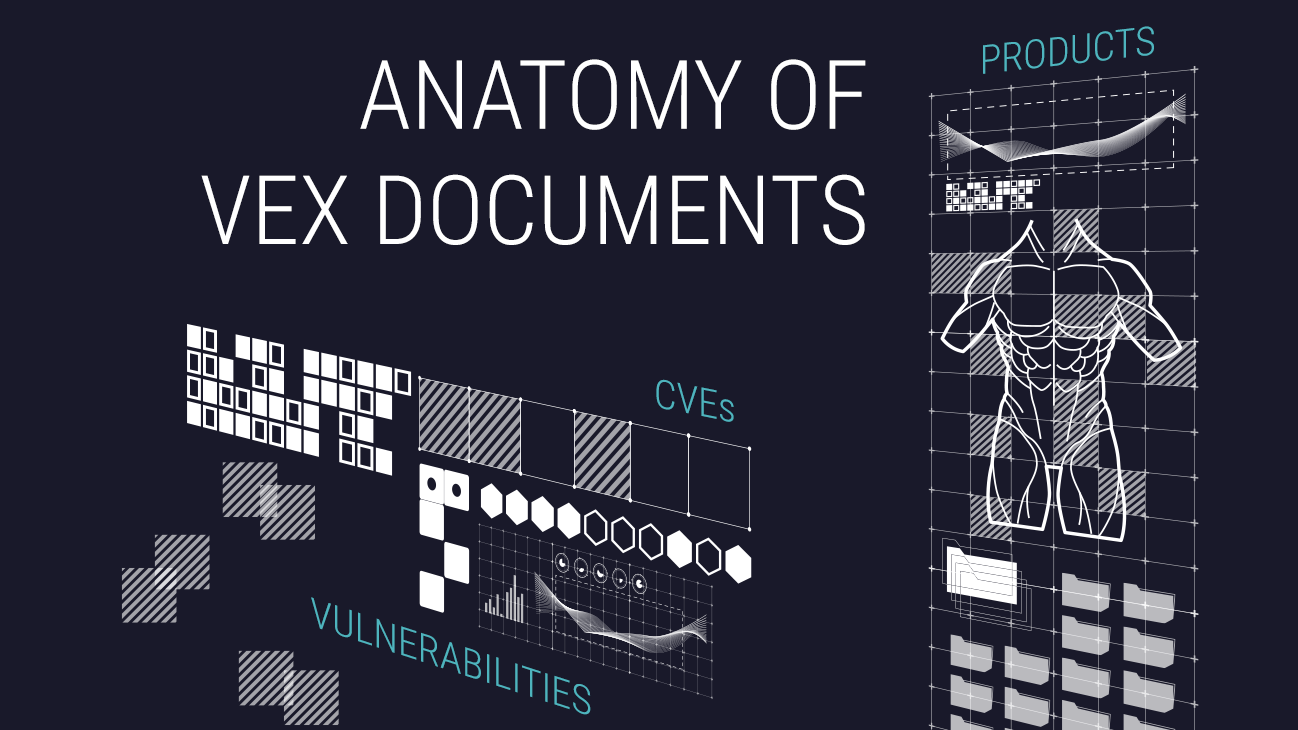

What we need is a way to coordinate the information about the software we use in our critical systems. For example, if you are using an SBOM to determine the components in a software package, you also want to be checking the signing of those components. If you deploy a traffic analysis service on your networks and it detects a software package being transferred, you want to understand the risk that software might introduce into your system. And you’d want to know immediately if the reputation of that software changes for any reason.

This isn’t something that we can do as individual companies. We need cooperation on software threats and vulnerabilities across companies and sectors. We need coordination between vendors, users, and consultants. And we need that cooperation to be in real time, not after the fact.

To put it another way, we need to get more eyes on the problem. And we need to have those eyes working as a team on a 24/7 basis. I believe that can happen only within a vendor-agnostic ecosystem for software information sharing — an ecosystem like FACT.

Eric Byres

Eric is widely recognized as one of the world’s leading experts in the field of OT, IT and IoT software supply chain security. He is the inventor of the Tofino Security technology – the most widely deployed OT-specific firewall in the world. When not setting the product vision, or speaking at a conference, Eric can be found cranking away on his gravel bike.

Stay up to date

Browse Posts

- May 2024

- February 2024

- December 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- October 2022

- April 2022

- February 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- January 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- November 2018

- September 2018

- May 2018

Browse by topics

- Supply Chain Management (16)

- SBOM (15)

- Vulnerability Tracking (15)

- #supplychainsecurity (10)

- Regulatory Requirements (10)

- VEX (8)

- EO14028 (6)

- ICS/IoT Upgrade Management (6)

- malware (6)

- ICS (5)

- vulnerability disclosure (5)

- 3rd Party Components (4)

- Partnership (4)

- Press-release (4)

- #S4 (3)

- Software Validation (3)

- hacking (3)

- industrial control system (3)

- Code Signing (2)

- Legislation (2)

- chain of trust (2)

- #nvbc2020 (1)

- DoD CMMC (1)

- Dragonfly (1)

- Havex (1)

- Log4Shell (1)

- Log4j (1)

- Trojan (1)

- USB (1)

- Uncategorized (1)

- energy (1)

- medical (1)

- password strength (1)

- pharmaceutical (1)

Post a comment